Dance Review: The Australian Ballet's 'Faster'

Physicality prevails in the Australian Ballet's 2017 Triple Bill, Faster.

This month The Australian Ballet debuted another ambitious contemporary triple bill akin to last year’s remarkable Vitesse, 2015’s 20:21 and the musically diversified Chroma from their 2014 season. However whilst this year’s production features some familiar choreographers, FASTER is an innovative and thematically-curated exploration of athleticism, and the triumph and expense of physical prowess.

Faster

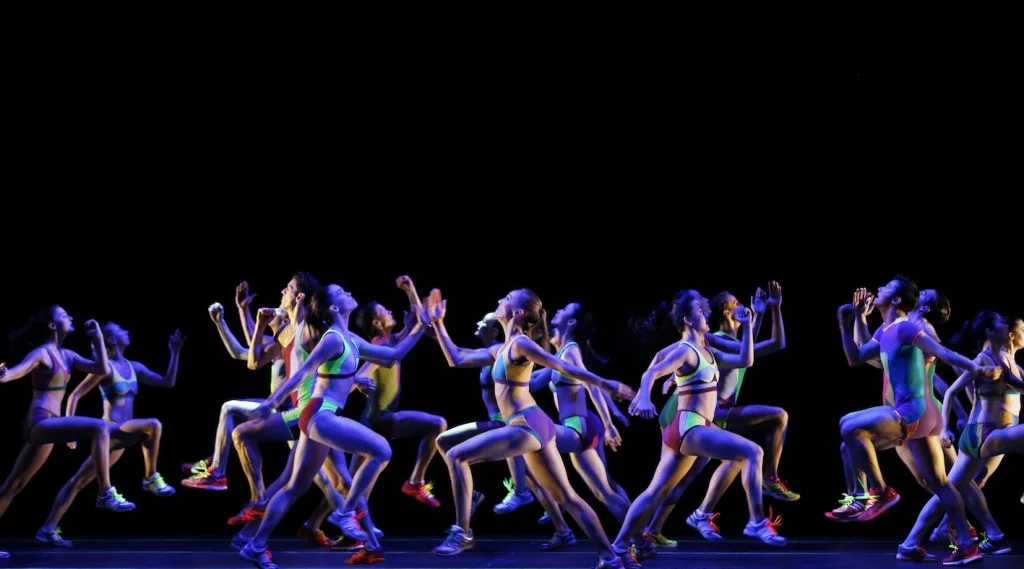

Enthralling from the very first note of music (executed with adrenaline-inducing potency by the Orchestra Victoria), composer Mathew Hindson creates a perfect tension that matches Choreographer David Bintley’s momentum beat for beat. Commissioned specially for the London Olympic Games in 2012, Faster is evidently an homage to athletes of all disciplines, with dancers clearly identified in fencing, swimming, running, and various other competitive attire. The pace is relentless from the onset, and it seems that Faster is less concerned with the performance of physical sport itself, as it is with humanity’s pursuit of it; as on-stage dancers strain, fight and struggle for the fleeting moments of enacted victory. It’s certainly a thrilling spectacle to witness as an audience, particularly with Becs Andrews brightly-hued costuming making each dancer a magnetic burst of colour against Peter Mumford’s relatively muted backdrop. However the piece does possibly miss an opportunity to truly integrate the ballet artform with it’s competitive counterpart, as the choreographic dialogue seems primarily concerned with emphasising the disparity between dance and sport, rather than the affinity of it (we repeatedly witness the strain, the burdens, and the celebrations - aspects pointedly masked in dance). Amber Scott’s Pas de Trois with Nathan Brook and Richard house (the ‘Aerialists’) makes audiences both awed and a little apprehensive as every facet of emotion and strain experienced by the performers throughout the largely-acrobatic feat can be witnessed on their open faces.

Jarryd Madden, Amber Scott and Richard House in David Bintley's Faster. Photography Jeff Busby

During another particularly vigorous point when all the female ‘athletes’ return to the stage in runners, crop tops and biker shorts to enact a race, the music abruptly halts and the dancers collapse forwards to lean on bent knees and take several fast, emphatic pants collectively… a sight entirely foreign to ballet audiences. For whilst this ‘recovery’ is indeed a common and natural part of an athletes performance, it’s sacrilegious in the world of dance. This makes the spectacle both incredibly entertaining and mildly disconcerting. Perhaps that’s exactly what Bintley intended, and if you’re able and willing to disconnect from the expectations of some of ballet’s inherent ‘laws’ and embrace the narrative and unconventional approach of a performance that focuses more on the flesh and bone ‘human’ aspects and less on the artists in it’s repertoire, then you’ll thoroughly enjoy this electrifying tribute to the power of human bodies and the human will.

Heidi Martin and Jacqueline Clark as 'Fencers' in David Bintley's Faster. Photography Kate Longley

Image: Jeff Busby

Squander and Glory

Image: Jeff Busby

The sustained tension and velocity continues through resident choreographer Tim Harbour’s atmospheric contribution Squander and Glory, which makes a rousing impression as the curtains lift to reveal an apparently expanded space - a group of dancers (or is it two?) poised on stage left; the mysterious, triangular form that architect Kelvin Ho and Lighting Designer Ben Cisterne have engineered to appear inexplicably hovering in space; and finally the most shocking of all - ourselves, as an audience reflected back at us. When the piece gets underway with an ominous clap of thunder and the orchestra’s resonating strings (the beginning of Michael Gordon’s Weather One), it becomes evident that the ‘floating’ object is cleverly suspended behind a semi-sheer reflective screen. Thereby superimposing itself between us and our own reflection yet not inhibiting the dancers' space. Overall the visual elements of the set, lighting and design make Squander and Glory endlessly enticing to look at, and similarly to Faster, there’s something slightly unnerving about the audience as spectators becoming part of the spectacle.

Artists of The Australian Ballet in Tim Harbour's Squander and Glory. Photography Jeff Busby

Resident Choreographer Tim Harbour’s movements are expansive, and often demonstrate a pressurised sharpness that reveals the incredible momentum underlying both the dancer’s actions and Harbour’s concept for the piece. Squander is loosely based on an essay by French philosopher Georges Bataille, in which he postulates that excess energy in our physical bodies must unequivocally be used up …one way or another, and Harbour’s exploration of this involves razor-like movements and directional changes (often favouring diagonals) that highlight the physical agility of the his dancers. Unlike Faster’s ode to physicality though, there’s a greater sense of unity and a shared intention between the fourteen artists on-stage. The choreography is frequently fractionalised, but audiences are still left with the impression that the dancers are acting as part of a single amorphous organism, or at the very least guided by a shared purpose. Midway through – just as the unrelenting pace of movement starts to overwhelm the captivating visuals of the set, the lights are brought up in the auditorium, bringing the reflection of the audience prominently in to focus once more.

The Australian Ballet dancers rehearsing Squander and Glory. Photography Kate Longley

Harbour is quite renowned for his innovative and unique choreographic methods – not least of which is his preference of ‘bringing the movement to the music’ fully-shaped, rather than allowing movement to be informed by the music (a technique with a track record of phenomenal results for him). However with Squander this does lead to some moments of incongruity. Rather than a performance that ‘responds’ to the music, the dancers can seem irreverent to it. Yet this is also it's bravest statement, instead of being at the mercy of an external catalyst, Squander's dancers are governed by a different force, something much more internal; and every gesture on-stage serves to convey the acuteness with which that catalyst (energy) manifested in physical power must be expelled on the journey to glory - and it makes a glorious journey to watch.

Photography Kate Longley

Infra

Jarryd Madden and Robyn Hendricks in Wayne McGregor's Infra. Photography Jeff Busby

The third and final performance of the evening, Wayne McGregor’s ‘Infra’ is also the third work by McGregor to be performed by the Australian Ballet (after ‘Dyad 1929’, and ‘Chroma’), and three is definitely the magic number. Created for the Royal Ballet in 2008 and awarded the Prix de Benois for the Year’s Most Outstanding Work, Infra was inspired by McGregor’s desire “to see beneath the surface of things: beneath the surface of a city” which is an intriguing concept with flawless execution. Immediately poignant, the emotional temperature of the evening thaws out dramatically from the earlier works as German composer Max Richter’s hauntingly beautiful score permeates the auditorium. This cinematically musical composition is aided by sound designer Chris Ekers' work, and set design by Visual Artist Julian Opie, whose scrolling digital figures are projected on a stage-wide screen suspended above the dancers. What’s engaging though is that Opie’s figures - who travel somberly from one side of the stage to the other - aren’t merely automated, but operated in real-time, so that each performances' outcome varies just as it does for the dancer (these figures are actually the result of earlier paintings Opie made of each of the dancers performing in Infra, reduced to a simplified pixel-form).

If this sounds distracting though, it isn’t, the musical elements harmonise perfectly with McGregor’s choreography. And Opie’s LED figures, in spite of their impressiveness, pale in comparison to the utterly seductive choreography being performed with emotional gravitas by the Australian Ballet. Rarely do more than two or three dancers take their turn on stage at a time (with two notable exceptions), emphasising a sense of emotional distance and isolation. The score is hauntingly delphic, both tragic and uplifting; hopeful and despairing at once. Unlike both Faster and Squander and Glory, McGregor focalises a certain physical vulnerability over physical strength, and this is realised through undulating, fluid movements that are immensely gratifying to watch as the adept dancers on-stage make the most of pliant limbs and oscillating gestures that articulate every impassioned note. Conceptually, it's a work that aims to examine the interior complexities of the emotional landscape, however it's easy to forget about themes or narrative when watching, which as McGregor reminds us, is perfectly alright: - “The big mistake of dance is saying all the time, ‘What does it mean?’ Meaning should be much more transient than that". Yet with McGregor's choreography being every inch the sinuey, nuanced movements that have come to be a trademark of his work, a spectacular score from Richter, and a masterful performance by the Australian Ballet Company making this the standout piece of the night, you may very well wish that Infra itself was just a little less transient.

See The Australian Ballet's Faster at the Sydney Opera House from April 7th until April 26th.

Book here.

Article by Elly Ford