Ballet 101: The art of Pirouettes

Ah yes, the humble pirouette. The one dance move that is universally known by all, and imitated (with varying degrees of success) by 90% of people whenever you happen to mention you're a dancer. So it's little wonder that for most of us, pirouettes are a pretty big deal, right?

Try getting through any ballet in history, or any audition anywhere without performing a pirouette and you'll realise just how important good turning technique is. For most dancers, from the moment we do that first successful turn, we're dreaming about the next one, imagining a double, hoping for a triple, fantasising about quadruples and yearning to one day be gliding around en pointe whipping out endless fouettés like the next Maria Kochetkova... And whilst you may or may not have achieved some of these milestones already, pirouettes are one of those things that can always be improved. Don't sweat it though, we've broken down all the important (and not so obvious) things that will help you to improve your pirouettes at any stage, whether that's mastering a double, or perfecting those triples on pointe!

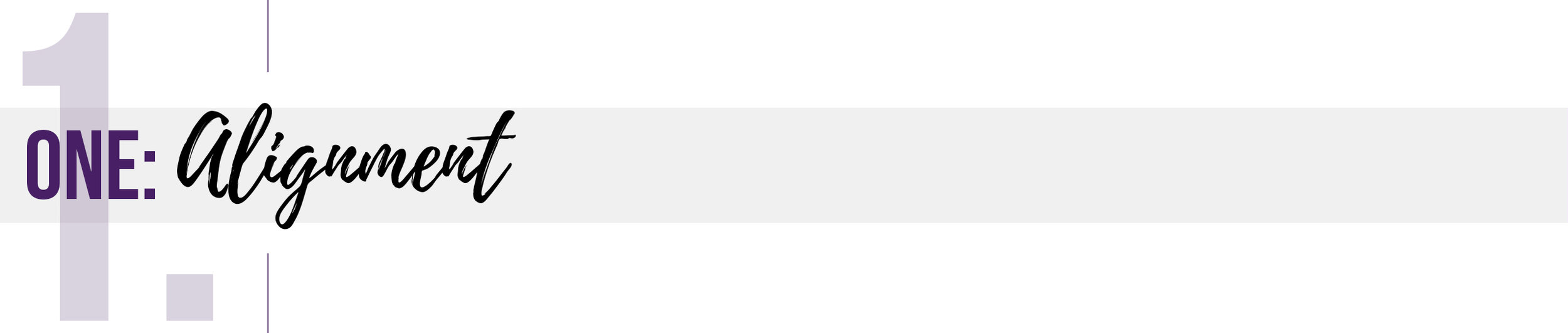

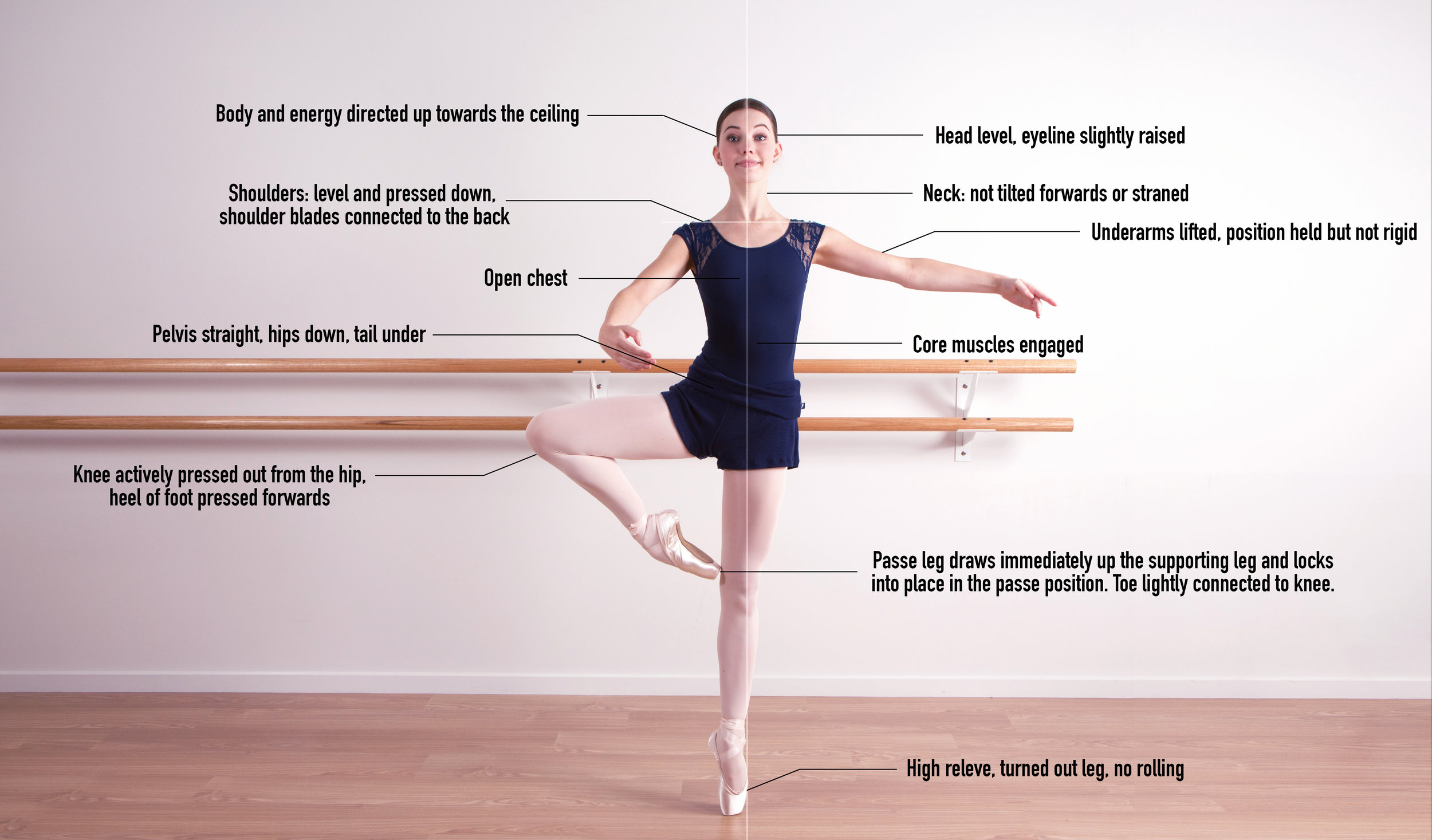

First thing's first; Despite the fact that a ‘pirouette’ means ‘turning’, a large portion of the skill and effort of achieving beautiful pirouettes has nothing to do with the rotation. In fact, spinning is probably one of the easiest components of a pirouette; it’s the spotting, preparation, correct placement and balance that really make the magic happen. So if you’re serious about improving your pirouettes it’s crucial to have a good understanding of exactly what your body is getting up to without the turn involved:

quick precise relevé

sharp spotting with the head

neck straight and lengthened

eyeline up

shoulders down and open chest

shoulder blades connected to the back

core engaged

arms lifted from underneath

firm port de bras position

working hip pressed down, parallel with the ground

pelvis tucked under

working leg activated and turned out from behind

knee high and activated to the side

working foot connected firmly with supporting knee

body directly over the line of the supporting leg

straight supporting knee, leg muscles pulled up

high demi-pointe in the relevé

no rolling or pronation of the foot

...And that's just once you're in relevé! Now let's break down what to do with all that information, and how improving your technique will enhance your turns:

Technically speaking, pirouette means ‘a whirling about on one foot’, which doesn’t sound so complicated when you put it that way. But as we've just demonstrated, that’s just the tip of the iceberg… First of all, forget whirling anywhere if you're off balance, and of course the longer you're balancing for the more crucial being completely 'on centre' becomes (you might be able to wing it around in a single pirouette, but there's 0% chance of landing an off-centred triple pirouette without gravity making a mockery of you.

Correct alignment allows you to maintain balance and stay on relevé throughout the turn, this means your head should be positioned directly over shoulders, shoulders over hips, and hips over toes. And don’t be fooled, it may seem logical that given the aim of balancing, your mission should be to stay as rock solid and unmoving as possible, but the opposite is true. The secret to balance is about being receptive to your body’s signals and making micro-adjustments accordingly. So how do you know if you’re allowing this pliancy as you balance? If you stand on demi-pointe and let a friend give you a gentle nudge, are you able to reassert your centre of gravity, or do you plunge towards the floor like a three legged table? If it's the latter, practise holding the relevé position and then ever so slightly 'tilting' yourself off balance. The aim should be to improve your ability to self-correct as smoothly and imperceptibly as possible whilst still maintaining good technique and improving your proprioceptive ability.

“The secret to balance is about being receptive to your body’s signals and making micro-adjustments accordingly.”

Yes, some good old-fashioned muscle power is essential for getting you around in a pirouette, but that doesn't mean just any old force will do; if you're unconsciously throwing your weight towards the direction you'll be turning in then you've set yourself up to be off balance before you've even begun to pirouette. Try and focus on an upwards force of energy, think elevation instead of lateral power. You should feel simultaneously that your foot is pressing downwards into the floor, whilst the rest of your body is pushing upwards towards the ceiling. This lengthening of the body will help keep you aligned as you turn, whilst still keeping you grounded through your metatarsals, helping you maintain balance.

Boost the support: A great way to give yourself the most stable foundation possible is by strengthening the supporting leg and ankle so that you're secure and steady in your relevé. Try ending each class with some rises at the barre: keep one foot in cou de pied (held at the base of the ankle) whilst your supporting leg rises slowly from flat to demi-pointe, hold, then lower until the heel is almost touching the ground and repeat again approximately fifteen times before swapping to the other leg. Make sure you're not neglecting the rest of your body whilst you do this though! Both feet should be well turned out, the core should be engaged, look ahead of you (not down at your foot) to maintain good posture and don't lean your weight on the barre. A good way to prevent this is by only resting two fingers from each hand lightly on the barre as you rise, allowing you to get the most out of the exercise.

A flow-on from the previous point; pirouettes are about focus, not force. Whilst sheer willpower can do a lot of things, demonstrating your determination to do a good pirouette by throwing as much force as you can behind the turn isn’t the best way to show it (...or finish upright). Like everything else in ballet, turning requires a balance of strength and restraint. The power of a dancer comes from the way they exercise their control, rather than just putting their full force behind everything. If a dancer’s technique is good and they’re using correct alignment and balance, even a fractional amount of force will provide enough torque to carry the body around in a pirouette.

Try: re-focusing some of your energy on co-ordination rather than force. You should aim for the working foot to reach passé position at the exact same time your arms move from fourth to first (or your turning position). This minimises the amount of momentum lost whilst you are transitioning from the preparatory position into the pirouette.

Don't forget your turnout isn't just there for decorative purposes! Pirouettes in fact are where good turnout can be of particular advantage (especially during fouettés). There's two main aspects of turning that turnout will affect when talking about pirouettes: firstly, when transitioning from the preparation position into the turn, dancers with limited turnout (or limited control) often allow the heels to slip out and the feet to become almost parallel without even realising it. Unfortunately, this can reduce the amount of torque (turning momentum) gained from the preparation. Secondly, the placement of the leg in passé: The turnout of the working leg can help to propel you around if you aim to lead with the knee instead of, say, the butt-cheek. And this range of motion that you have - the capacity for lateral rotation in your hips - will impact how well you can turn out in the pirouette position. The good news is, if you're struggling to keep well turned-out when you pirouette, your turnout (ie. you hip's 'range of motion) is something that can definitely be improved. Whether you need to stretch your hip flexors (the iliofemoral ligament), or strengthen the posterior hip/leg/gluteal muscles, we've laid out some of the best exercises here: Turning out better.

'Practise makes perfect' is a mantra no doubt familiar to everyone who's ever taken a dance class, but it's worth noting that it's the kind of practice you're putting in, not the amount of it, that will ultimately determine how close to perfect you get those pirouettes. Standing in front of the mirror doing pirouette after pirouette without pause isn't really going to do you any good. In fact, you're likely to build bad habits without even realising. It's so much more beneficial for yourself and your body if rather than focusing on quantity, you focus on the quality of your technique with every turn. When you do get time to practice, use it to break down each step and notice areas you may need to focus on. Maybe you only do fifteen pirouettes that day, instead of fifty, but by the end of the week you will have started to build new, better muscle memory and have begun to over-ride any bad habits that had become entrenched through repetition. Soon your body will automatically know what correct placement feels like and good technique will no longer be something you have to 'apply' to your pirouettes. It will be second nature.

On a related note, have you ever watched a company class and noticed how no matter the speed of the exercise, professional dancers never seem to be in any hurry - they always gauge their pace so that they have enough time to take their preparations as serenely and un-hurriedly as possible, before gliding around like they have all the time in the world. This is because they know that the tempo you perform an exercise at should vacillate between quick, efficient movement in transitional steps, and sumptuous fluid execution for key steps, and at the end or 'peek' of a movement. This helps to emphasise certain moves and give the dancer the maximum amount of time on their pirouette rather than the pas de bourrée before it, for example. It also makes an exercise far more dynamic to watch than one where every single movement is performed at the exact same pace. Check out this Royal Ballet Company Class for a great example of how the time dancers take for steps will fluctuate between sharp, fast transitional steps, and more deliberate, controlled movements and think about this next time you're doing an exercise in class.

Please excuse us for how many times we're going to say preparation in this paragraph (and this post)... but hopefully the repetition sinks in, because your preparation is everything! Whilst Benjamin Franklin probably wasn't talking about ballet when he said “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail”, it certainly rings true for pirouettes, and dance in general. Making a good preparation a habit is a crucial step in mastering pirouettes so that the correct posture, weight placement and alignment comes naturally as soon as you take that establishing plié. And what is the correct weight placement you may ask? Well, whether you take a Balanchine preparation in fourth (front leg on plié, back leg straight) or the traditional demi plié (both knees bent), your centre of gravity should always be over the front (and soon to be 'supporting') leg. It might at first feel more comfortable to keep your weight balanced over both legs, but if you're not properly prepared for that relevé that's about to come... game over. Keeping your weight between the two legs, or on your back leg - big no-no - means that when you do have to quickly transfer to the front leg as you snatch up on relevé, the only way your body can keep you on balance is by throwing the chest, arms and head forwards. And once you combine this with the fact that you've also begun to rotate as you start the turn, your weight is going to pitch you off balance immediately (that is unless you then stick your butt out to compensate - yes that is why that's happening!). This in turn means your core will be disconnected and you'll have very little control over what happens (or where you end up) next. So you see, it's all one big anatomical flow-on effect, and it all starts with a plié.

Left: incorrect posture (head and neck forward, arms not lifted from underneath, core disengaged, bum sticking out and pelvis tilted forward, which causes bad alignment. Right: improved posture (head and neck in line, chin level, arms lifted from underneath, chest over hips, core engaged, pelvis tucked in, gluteal muscles activated.

Another tip: don't pre-empt the turn when you're in a preparation (an especially common mistake from 5th position pirouettes to get that extra impetus). What do we mean? Well one error dancers can make when 'preparing' to turn is instead of focusing on the technique of a good preparation, they're already thinking about getting around in the turn, and as a result they unconsciously shift their bodies in anticipation: their neck and head comes forward, the bum sticks out and the arms swing across the torso to give that additional turning-power (this is what teachers are talking about when they remind you to turn with your body, not your arms). It should be the rotation of the torso that carries the arms (connected via your engaged back and shoulder blades) around once in the relevéed position, not the other way around. How can you tell if your arms are doing too much of the heavy lifting? Simple, do a pirouette. Now do the same pirouette but with your arms going straight to fifth position. If you struggled significantly more without the momentum of your arms in first position to help you get around then you've probably been over-using them.

A final tip to watch out for with your preparation: Don't 'double plié', the transition from whatever previous step you've done into the plié and then into a pirouette should be one smooth, seamless motion. Don't stop to 're-prepare' or adjust the feet before you turn, as it breaks the flow of the exercise and just lets you be less disciplined with the precision of your placement. It might take a while to break the habit of re-correcting each time, but once you do, it's worth it.

This might sound a bit hypocritical given that I've just spent the past few minutes giving you plenty of things to think about whilst pirouetting, but there's a difference between having 'technique in mind' and getting so overwhelmed by the technicality that you're not even thinking about doing 'a pirouette' any more, but rather 700 tiny, improbable acts of physics laid out in a precise order of impossible steps. Instead of letting everything bombard your brain in the middle of a pirouette exercise, the best thing to do is take your time with your preparation; breathe; think about your alignment and what you want to happen once the turn starts. Visualise your working leg snapping into place on the inside leg, feel your core engage and your shoulder blades connect to your back, feel yourself pulling up all the way from your ankles and out the top of your head, then take another breath and let your body do it's job. The time for analysis is before and after you do a pirouette, but whilst you're actually performing the step allow yourself to be in the moment and feeling exactly what your body is getting up to. This is what will allow you to go from reciting the steps of a perfect pirouette to feeling it first-hand.

Make the most of your practice time by using it effectively; know when to push and when to stop.

Also, a little reminder to take it easy on yourself too. Everyone has off days, and considering just how complex a good pirouette can be it's no wonder that off days can often involve treacherous turns. It's really important though that you don't allow this to upset or frustrate you, because without a clear head it's easy to revert to old habits, or even worse, become so worked up by 'failing' that you create an even bigger mental block for yourself. What might have started out as just a single misplaced turn can end up becoming a whole mental hurdle that takes you weeks to break. If something just isn't working in class one day there's nothing wrong with setting it aside, clearing your head and coming back to it a little later when there's no adverse emotions clouding your judgement. As dancers we're always told to push through and keep going no matter what, and this can be an effective way to build physical stamina. But when it's your mental energy that's exhausted, it's not muscles you're building by being unrelenting; you're just weaving all of that emotion, frustration, unhappiness or whatever else you're feeling into a big barrier that you'll have to break down every time you come back to this step. So be kind to yourself, and be wise with your time. Don't feel compelled to spend it on practice that isn't a productive use of time.

One final tip for you all, my ballet teacher always used to say 'the audience never forgets the ending', and drilled it into every student that no matter what happens during a performance (or a pirouette) always, always, always finish with complete grace and confidence. Even if you landed on your butt, came off pointe, forgot to spot, lost your balance; stand up, be proud and give them a finish to remember, because the last few seconds of a dance are the moments that last forever.

Now good luck with those pirouettes!

Article by Elly Ford